Time-Saving Hacks for Efficient Grading Part 1 : A CTE Workshop Recap

In October 2020, the CTE ran a panel discussion on time-saving hacks for grading efficiently. Lauren Boasso, Stephanie Gillespie and Kristen Seda

On October 29, 2020, the CTE ran a panel discussion on how to use student input to shape your course. Many thanks to Maria-Isabel Carnasciali, Matt Schmidt, and Mary Isbell for offering diverse, thoughtful perspectives on the topic. For those who couldn’t make it, check out our recap below of some strategies from the presentation. You can also visit myCharger to view the recording.

Why should I ask my students for input?

Checking in with your students allows you, as the instructor, to learn what’s working for your class and what’s not. It gives the instructor opportunities to understand challenges students are facing and may inspire new or additional ways to support students. Feedback can also reveal confusion regarding course policies and expectations that might not otherwise be revealed in the usual flow of the course. This can improve (or open) lines of communication that weren’t there before.

Asking for input also allows students to become co-producers of learning, rather than just consumers. Students appreciate voicing concerns and opinions when adjustments are possible, and they’re more invested in their work when they contribute to the course development (Bovill, Cook-Sather, and Felten, 2011). On behalf of the instructor, it also shows a commitment to helping students master the subject matter and acknowledges that each group of students has different needs.

Ways to get student input

What to get feedback on (the best part is you get to choose!)

Best Practices

Methodologies

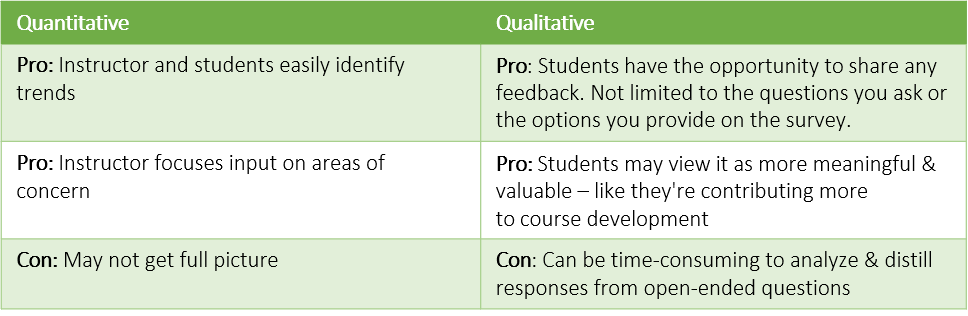

As you draft your approach to gathering input, consider whether you’d prefer to get quantitative or qualitative data. There are pros and cons to both. Quantitative data sets make it easier to identify trends if you have a large number of students. However, quantitative data doesn’t always provide the full picture of student experience. Qualitative data allows students to share about their experience in their own words. Research has also suggested that when students get to offer qualitative data, they feel like they’re contributing more to course development and they may view the feedback experience as more meaningful (Hoon, Oliver, Szpakowska, Newton,2015).

You might consider doing a little bit of both! Ask a few multiple-choice questions and included an open-ended question as well.

A holistic vision. Maria-Isabel Carnasciali, Associate Professor of Mechanical Engineering, will cue students in to her feedback plan from the start. In her syllabi, she mentions how feedback will shape the course. Early in the semester, she will also share suggestions/feedback from the prior term – including end-of-term course evaluation items – that she will and will not be putting into effect. She will even share citations or references that back up a methodology for learning. Carnasciali says, “I believe it builds confidence in the students that I do value their input and that it matters. As a result, I think they carry this throughout the term, including into the end of term evals.”

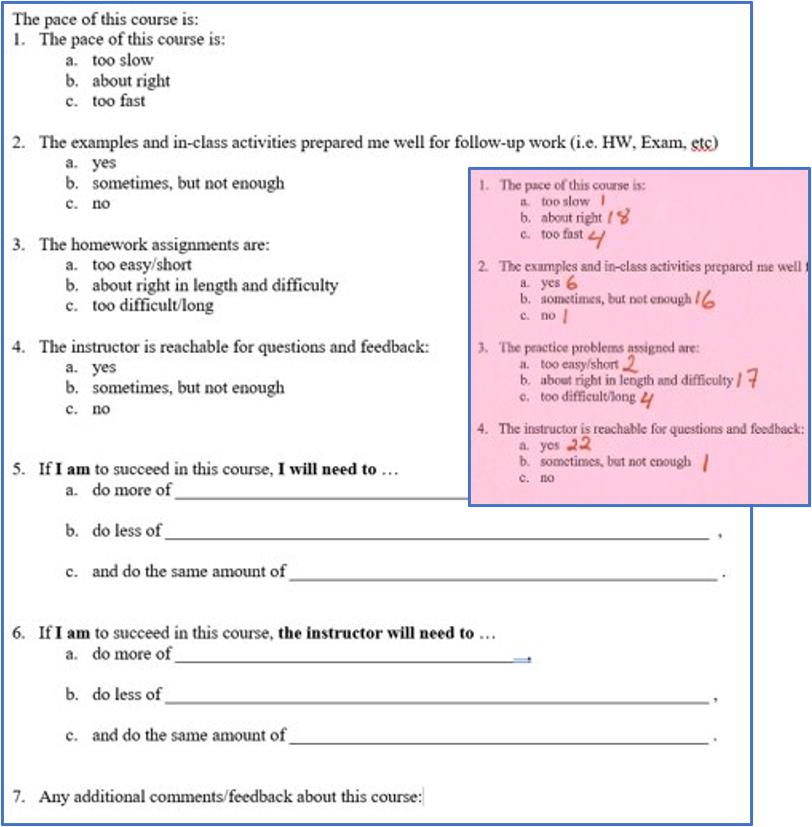

Carnasciali will use the following informal in-class survey to get prompt feedback from her students:

Quick pulse check:

She has also used a more formalized Mid-Term Feedback form to gather some bigger picture information about the course. She finds asking students to complete this right after a mid-term project will help students be more realistic and honest with their feedback. The corresponding image in pink shows her tallied data.

Impacting course content. Matt Schmidt, Associate Professor of National Security, uses student input to directly impact course content. He believes “Content is not the most important part. The classroom is a social space that needs to allow for emotional security when a student says, “I don’t know.” He uses his classroom as a space to help students figure out what they don’t know, and they make a plan together on how to fill the knowledge gaps throughout the course.

He and his students work together to uncover the path of their particular course through reflective writing, public grading, and having direct conversations with his students about how they’re doing in the course, and how it can be shaped to help inform their career aspirations.

Importance of audience. How can you plan to use content that your students can relate to when you haven’t met them yet? Mary Isbell, Associate Professor of English, asked herself this question, and changed her approach to course planning. She will build a set of resources and decide how to reference, assign and supplement them after she gets to know the students.

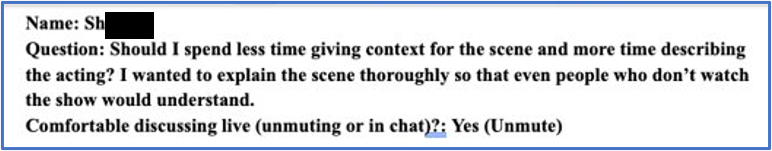

Isbell also believes, “Unless we ask, we really don’t know.” This especially rang true for her this semester as she faced a screen of empty black boxes representing her synchronous online classroom. Not being able to see her students made it more difficult to gauge their response to course materials and activities. Isbell shared with us a related anecdote.

Frustrated by the inability to see her students’ reactions, she asked about the lack of interest in being on camera, or using audio input in one of her frequent “How’s it going” surveys. She discovered some of her students were unable to turn on their cameras, or communicate with audio, because they had roommates asleep nearby. This prompted her to use the following framework to solicit participation from her students:

Additionally, after sharing a video interview that few students watched, she asked in a survey why they didn’t watch the entire video. She found out that they didn’t realize they had to watch the whole thing, and instead skipped to the part where their specific question was answered. These examples clearly illustrate how simply asking students for input can help clear up points of confusion, and strengthen lines of communication.

This is arguably the toughest part of getting feedback, but it is a necessary part of growing as an instructor. Reviewing the critical feedback gets easier with time. The benefit to checking in with your students throughout the semester is that you have the opportunity to make changes in real time and potentially improve the class experience for yourself and your students, instead of getting to the end of the semester and saying “I wish I had known…”

Beyond just asking for the input, sharing the responses with your class is crucial. This is where the course development partnership can be solidified. As mentioned, surveying the course indicates that you’re committed to helping your students succeed. Closing the loop and reviewing the feedback with your students gives you the opportunity to explain why certain policies are in place. This can include explaining why you won’t make certain changes that were suggested. It also allows the opportunity to give credit to students for good suggestions and to explain any changes that will be made based on their feedback.

Microsoft Forms

Learn more about using Microsoft Forms on LinkedIn. Topics include viewing results in excel and sharing the form as a template.

Suggestions:

Make sure it’s anonymous

Choose “anyone with link can respond”

Do NOT choose to Record name or Send email receipt to respondents

Invite students to respond by posting the form link, QR code, or embed code in an email or site

Canvas

Create anonymous surveys in Canvas using the quiz function.

Suggestions:

Be sure to select “Ungraded Survey” as the Quiz Type.

Once the quiz is marked as ungraded, you will have the option to keep submissions anonymous.

Helpful Readings

The Center for Instructional Technology and Training at University of Florida, Continuous improvement cycle four stages: Plan, Implement, Collect Information, and Analyze.

Center for Teaching at Vanderbilt University, What, Why, When, and How of collecting mid-semester feedback and what to do with it including turning these criticisms into positive changes

Center for Teaching Excellence at Duquesne University, Processing the Feedback from Your Evaluations

Works Consulted

Bovill, C., Cook-Sather, A., and Felten, P. (2011) Students as co-creators of teaching approaches, course design and curricula: implications for academic developers. International Journal for Academic Development, 16 (2). pp. 133-145. ISSN 1360-144X

Freeman, Rebecca & Dobbins, Kerry (2013) Are we serious about enhancing courses? Using the principles of assessment for learning to enhance course evaluation, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 38:2, 142-151, DOI: 10.1080/02602938.2011.611589

Hoon, A. and Oliver, E.J. and Szpakowska, K. and Newton, P. (2015) ‘Use of the ‘Stop, Start, Continue’ method is associated with the production of constructive qualitative feedback by students in higher education.’, Assessment and evaluation in higher education., 40 (5). pp. 755-767.http://dro.dur.ac.uk/13818/1/13818.pdf

Hunt, Nancy (2003) Does mid-semester feedback make a difference? Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning; Indianapolis Vol. 3, Iss. 2, 13-20.

Walker, Alicia (2012) The Mid-semester Challenge: Filtering the Flow of Student Feedback, Teaching and Learning Together in Higher Education: Iss.6, http://repository.brynmawr.edu/tlthe/vol1/iss6/4

In October 2020, the CTE ran a panel discussion on time-saving hacks for grading efficiently. Lauren Boasso, Stephanie Gillespie and Kristen Seda

In October 2020, the CTE ran a panel discussion on time-saving hacks for grading efficiently. Lauren Boasso, Stephanie Gillespie and Kristen Seda

In October 2020, the CTE ran a panel discussion on time-saving hacks for grading efficiently. Lauren Boasso, Stephanie Gillespie and Kristen Seda